Draper Speeds Planetary Science Discovery

CAMBRIDGE, MA – Proof of life within the ocean that lies beneath the surface of Jupiter’s moon Europa has eluded scientists since NASA’s Galileo mission ended in 2003. With approximately $2 billion set aside to develop a spacecraft destined to orbit Europa, NASA intends to probe its surface in the late 2020s.

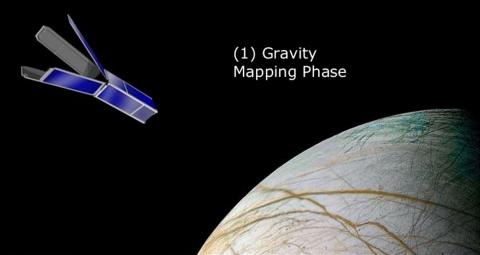

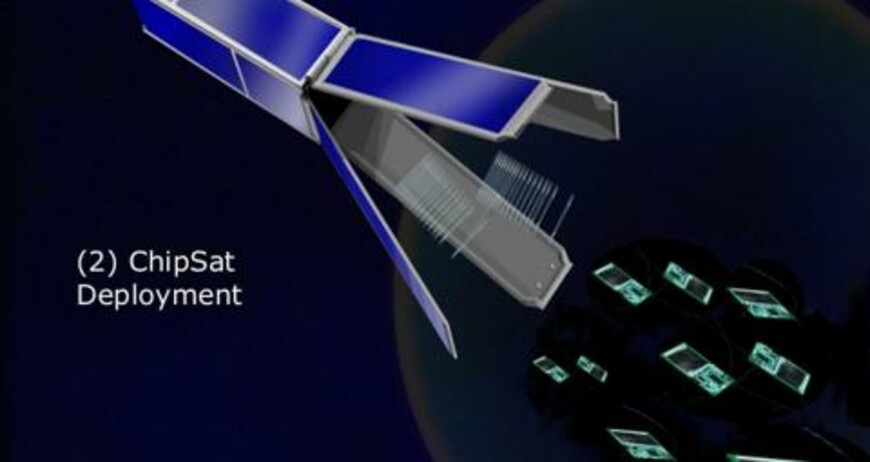

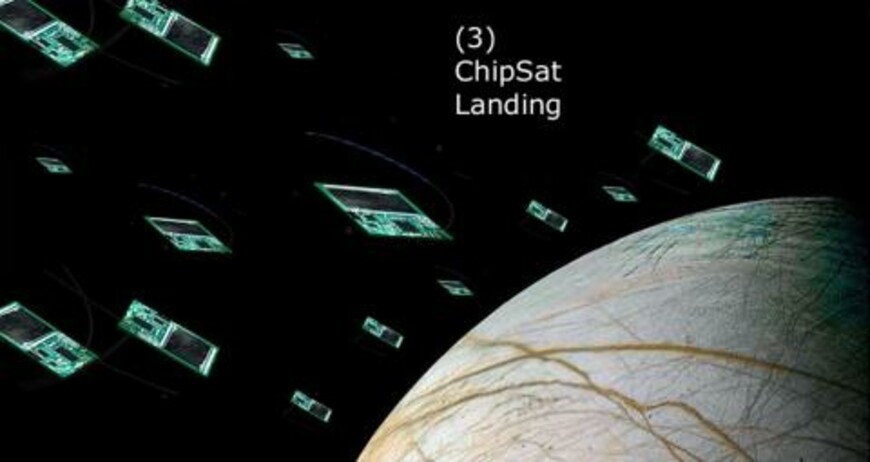

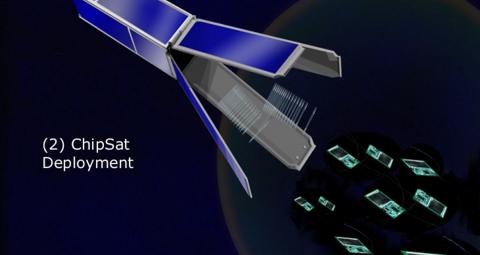

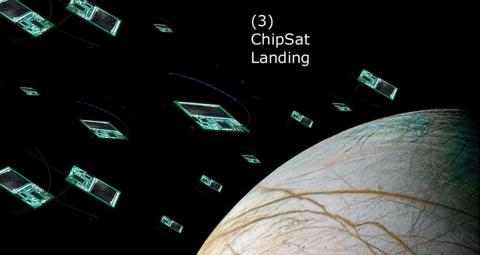

Thanks to Draper’s ChipSat solution, and at a cost of roughly $10 million, NASA could obtain the data it needs to bolster the success of its flagship Europa exploration. While orbiting Europa, CubeSats could take gravitational measurements to identify areas with the thinnest ice, and then deploy hundreds of tiny ChipSat sensors to examine the surface — providing the optimum location for probe delivery.

“As we make progress exploring the solar system, the data required to answer new questions becomes more complex, so a single observation becomes less likely to solve an open question as we return to planetary bodies that we have previously studied,” said Brett Streetman, Draper’s principal investigator for the dual exploration architectures project. Streetman presented a paper on Draper’s most recent progress on the concept at the IEEE Aerospace Conference in Big Sky, Montana, on March 9.

Draper began working on the concept in 2014 with funding from NASA’s Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) branch. Initial work focused on defining mission architectures that could benefit from this flexible approach and identifying technology gaps that needed to be filled. Draper has refined its focus on the Europa mission by creating an initial design for a CubeSat-scale cold atom gravimeter that can determine gravitational indications of thin ice, identifying the available suite of sensors that could reside on an impacting ChipSat, and studying the survivability of ChipSats impacting Europa. The company will continue to refine the ChipSat design, begin a series of tests prove impact survivability, and examine how to protect Europa from any Earth contaminants.

The concept could lead to the first use of ChipSats for planetary exploration. Draper is working with Cornell University to increase the viability of using ChipSats. Initial indications suggest that their small size and lack of moving parts may make them highly capable of surviving impact on a planetary surface without any dedicated protection system, Streetman said. The low cost of ChipSats would enable scientists to use a large batch, reducing the consequences of losing some upon impact, he said.

Additionally, this capability could provide a quick-response solution for researchers who study events on Earth that are difficult to predict, and thus difficult to reach quickly with personnel and in-situ sensors, such as volcanic eruptions and algae blooms, said John West, who leads advanced concepts and technology development in Draper’s space systems group.

With sufficient funding, Draper could complete the development of its ChipSat designs by 2018, and could begin field tests of workable prototypes in 2019.

Released March 15, 2016