The Military’s Next Drones May Use AI from Draper

CAMBRIDGE, MA—Military leaders want drones with greater autonomy, giving warfighters the ability to offload critical tasks. Advanced autonomy, however, has eluded commercial providers, despite attempts to achieve it. One approach may lie in developing artificial intelligence (AI) enabled unmanned aerial systems (UASs)—an effort underway at Draper.

Drew Mitchell, defense systems associate director at Draper, says the military is looking for systems capable of autonomous operation in highly complex, contested and congested environments. AI can enable UASs to perform tasks that normally require human intelligence, for example, recognizing patterns, learning from experience, drawing conclusions, making predictions or taking action.

“A new wave of autonomy-enabling software is giving warfighters a new tool for operating in conditions commonly found in combat environments, such as GPS-denied locations and battlespaces riddled with harsh electromagnetic interference. The new capabilities are making small unmanned aerial systems a force multiplier,” Mitchell explains.

Naval Surface Warfare Center, Crane Division has invited Draper to compete in its Artificial Intelligence for Small Unit Maneuvers (AISUM) Prize Challenge. Participants will be evaluated on the strength of their algorithms to maneuver an sUAS autonomously in and out of buildings and provide reconnaissance in a virtual simulation environment. The drones, sensors and onboard processors for the live demonstration phase of the challenge will be provided by the government, underscoring the importance of software to the new generation of sUASs.

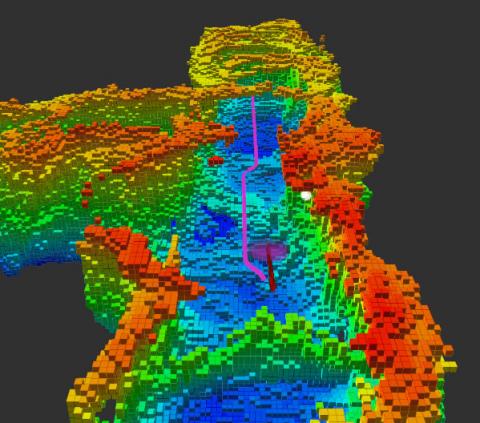

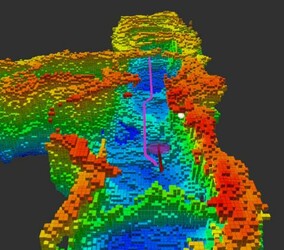

Draper described its sUAS system architecture in a technical white paper submitted in phase one of the challenge. The company’s special operations team working on the AISUM Challenge identified four key functions for future small unmanned aerial systems. The first function is high level autonomy, which encompasses motion planning and control, dense three-dimensional mapping and AI-based tracking and automated target recognition. Other functions are avionics, which includes the flight controller, high-rate sensors for collision avoidance, object detection and positioning and other systems to ensure stability and agility; and communications, which centers on secure radio communication and navigation.

A fourth function, operator interface, is given special attention because a well-engineered interface is critical for decreasing a warfighter’s cognitive burden and task load, which, the paper says, “is very high for current manually-operated sUASs.” Draper’s team of human-factors engineers developed an ATAK-compatible user interface.

ATAK is an application that is familiar to the warfighter, the paper explains. “It provides many hooks for sharing intelligence gained by the sUAS with other warfighters and command while on target, and provides the flexibility for the warfighter to choose from a variety of Android-based handheld controllers. Ultimately this enables the operator to customize their kit for optimal mission operation,” according to the paper.

In its design, Draper optimized its sUAS system architecture. Benefits include improved flight-control algorithms, better use of on-board processing power and progress in machine vision, artificial intelligence and other pattern recognition tools, which will allow an sUAS to handle more decisions, rather than relying on humans.

Draper employs intelligent autonomy through the All-Domain Execution and Planning Technology (ADEPT) framework. The ADEPT framework is a design concept which overcomes the challenges of the Prize Challenge through two key components: hierarchical task decomposition and a sense-reason-act paradigm of intelligence.

Draper’s intelligent autonomy software architecture is currently used on autonomous systems and applications for undersea, ground, air and space vehicles. An example of Draper’s work in this area is the Maritime Open-Architecture for Autonomy (MOAA), which serves as the foundation of the US Navy’s underwater autonomy architecture. Draper has also contributed to small UAS programs for a number of government agencies and the military.

About NSWC Crane

NSWC Crane is a naval laboratory and a field activity of Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) with mission areas in Expeditionary Warfare, Strategic Missions and Electronic Warfare. The warfare center is responsible for multi-domain, multi- spectral, full life cycle support of technologies and systems enhancing capability to today’s Warfighter.

Released June 8, 2021